A study appearing in has put a serious dent into the theory, referred to as the obesity paradox, that moderate increases in body fat are protective. In this 150 second analysis, F. Perry Wilson, MD, explains what makes this study more believable than the many that have come before.

Back in 2013, appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association:

This well-done meta-analysis looked at 97 studies that examined the link between body mass index and mortality, and found that, relative to those with a normal BMI, those with BMIs in the 25-30 range had a lower all-cause mortality. The weight of evidence, it seemed, confirmed an "obesity paradox" whereby people with higher BMIs lived longer. Cue the lay press with articles like from TIME magazine, speculating on the benefits of body fat:

And from Prevention, identifying four situations where you're better off if you are overweight.

But a persistent chorus of researchers asked if maybe this finding was an artifact of poor measurement. Maybe people who are sick, even if they don't know it, lose weight, inflating the risk of mortality in the normal weight group.

Well, that theory got a king-sized helping of facts from , published in the Annals of Internal Medicine:

Using data from three large cohort studies, comprising over 225,000 individuals, the researchers demonstrated that, no, there was no protective effect of being overweight. In fact, there was a small, but significant, added risk for all-cause mortality.

What did this study do that the 97 in that meta-analysis didn't? They looked at maximum weight achieved over the past 16 years in addition to current weight. This helps to account for those people that lost weight due to underlying, perhaps undiagnosed, diseases.

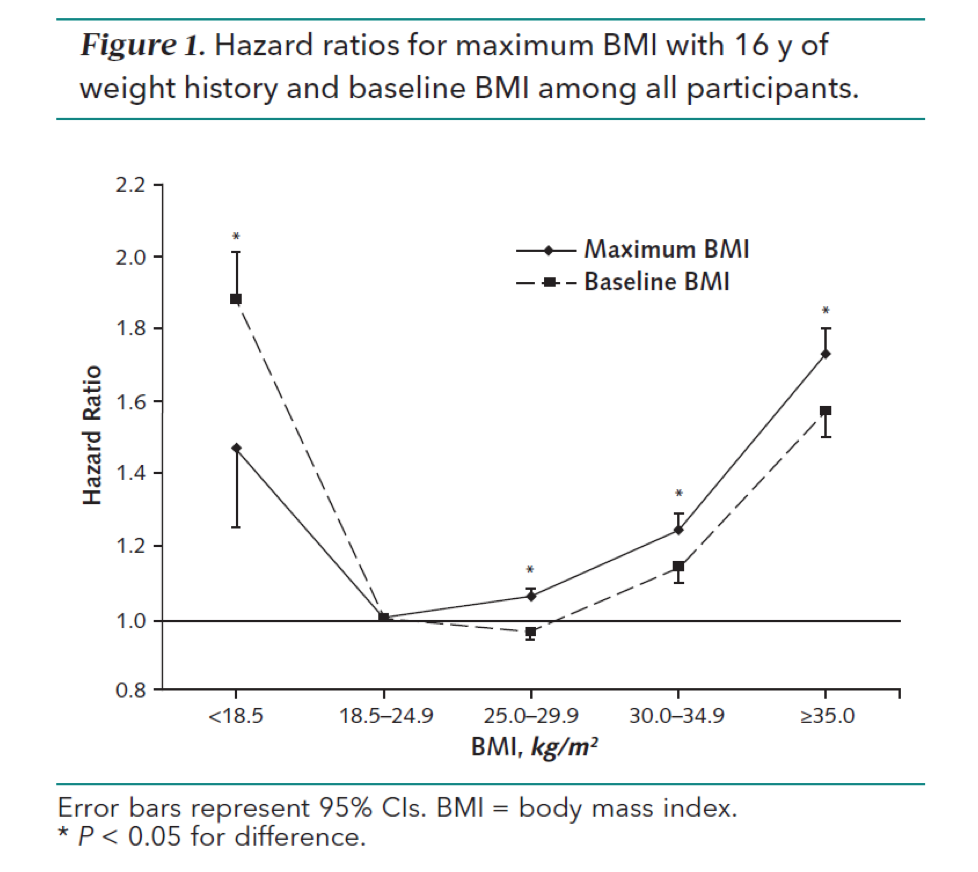

And when they did that, they found this relationship between BMI and mortality:

In the dashed line, you see the hazard ratio for mortality associated with the various BMI categories based on the single, most-recently-measured BMI. Note the slightly reduced risk among those in the overweight category compared to the normal weight category.

But when maximum BMI was used, the paradox disappears. Overweight individuals have slightly increased risk compared to those in the normal range.

To drive home the point, the authors looked at change in weight, and the results are just what you'd expect. People who lose weight were at much higher risk of death than those who did not, regardless of what their BMI was to start with. In fact, those who had a normal BMI at the most recent weight check, but who had been overweight in the past had a 19% higher risk of death than those who stayed overweight the whole time. This doesn't mean that weight loss is bad for you. It suggests that weight loss is a sign of underlying disease.

The healthiest people were those that had a normal weight all the time.

The take-home here is that a single measurement of BMI at one timepoint may not be that useful. Trends in weight are much more important. And unintentional weight loss is a major danger signal. After all, we all know how hard it is to lose weight when you are really trying to. If your patient is losing weight without putting effort into it, it's time to look a bit deeper.

, is an assistant professor of medicine at the Yale School of Medicine. He is a ľ��ֱ�� reviewer, and in addition to his video analyses, he authors a blog, . You can follow .